Blog

7 Simple Techniques for Writing Better Melodies

29 Jun '2023

Step up your melody game and start writing earworms with these no-nonsense tips

There are many elements of a song that can make it stick in our memories and cause us to return to listen to it time and time again. Maybe it’s the vocal delivery of the singer or their lyrics, or maybe it’s the infectious dual groove of the drums and bass that hits home. More often than not though, it’s melody that catches our attention.

A well-written melody can be timeless, like Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday” or Harold Arlen’s “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, and enjoyed by people the world over. Catchy melodies don’t necessarily have to be complex, as proven by nursery rhymes and children’s songs like “Baby Shark” (sorry), or require in-depth music theory knowledge to write. However, that doesn’t make melody writing an easy process, which is why we’ve compiled a list of top tips to help you write better melodies.

Use notes from your chords

If you’ve got a chord progression locked in, but no melody to go with it, one way of finding the right notes is to choose pitches from the chords themselves. On each prominent beat your melody could take one note from the chord being played, for example. One thing to remember is that the root and fifth note of any chord are always the strongest and most distinctive to use.

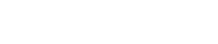

Working in a DAW brings certain advantages for melody writing, with one being the use of MIDI. Whereas audio displays as a waveform in your DAW, MIDI is represented by notes distributed across the piano roll. By clicking into a MIDI clip, you can take a closer look at melodies, picking apart a phrase by moving the notes around to affect pitch, timing, and duration.

If you’ve got a nice chord sequence but you’re struggling to find a melody that fits over it, try copying your chords to the MIDI track that’s set up for the melody. You can then solo one note for each chord by muting the others with your DAW’s mute tool, or removing them from the MIDI clip entirely. Solo different notes and shift them to different octaves or timings until you find a solid basis for a tune.

Try stepwise motion

A step is the difference in pitch between two consecutive notes of a musical scale. For example, in the scale of F major, F to G is a step. When the interval between any two consecutive notes in a melody is no more than a step this is called stepwise motion. Melodic motions that jump one note in the scale are called skips, and anything above that is called a leap.

In general, it’s a good idea to have about half to two-thirds of your melody made up of steps, and one-third to half made up of skips or leaps. Stepwise motion makes a melody easy to sing along to, as well as supporting rhythmic grooves. Lare melodic leaps, on the other hand, should be saved for dramatic, high-impact moments when you want to excite the listener.

Experiment with motif writing

A motif is a short musical idea, not an entire section or movement, but also not just a single note, that repeats throughout a song. A motif can be repeated exactly the same, or also be developed so that it appears in a slightly different form than when the listener heard it first. You’ll hear this a lot in film scores, where the main musical motif is worked into the soundtrack at various moments.

Motifs can be melodic or rhythmic, and if they’re used in vocal parts can even be reflected by clever use of lyrics. Here’s a strategy you can use to develop your own memorable motif:

- Set up a chord progression

- Choose a scale that works over the chords

- Pick three or four notes in the scale and keep playing them randomly

- Change the distances between the notes

- Record the pattern

Try repeating this process three or four times, until you have a group of melodic motifs to choose between. Take a five minute break from what you’re doing and leave the room – the one that you can remember at the end of the break is the one to go with!

Switch up the rhythm

The importance of rhythm in melody writing shouldn’t be overlooked. Rhythmic interest makes things less predictable and is also a useful tool for directing the energy of a track.

Simple melodies can instantly be made memorable by spicing up the rhythm of the phrase with syncopation. Syncopation is the placement of rhythmic stresses or accents on non-important beats, where they normally wouldn't occur. It's a common feature of jazz, blues and hip hop music, although you’re likely to hear it in pretty much everything that’s around today.

Another way you can liven up a melody is by altering the placement of the notes so that they are slightly less rhythmically predictable. You don’t have to have melody notes landing right on the first beat of the bar, for instance. You could bring your melody in an eight-note ahead of the bar for a “pushing” feel (this might require you to move the other elements of the track forward too.

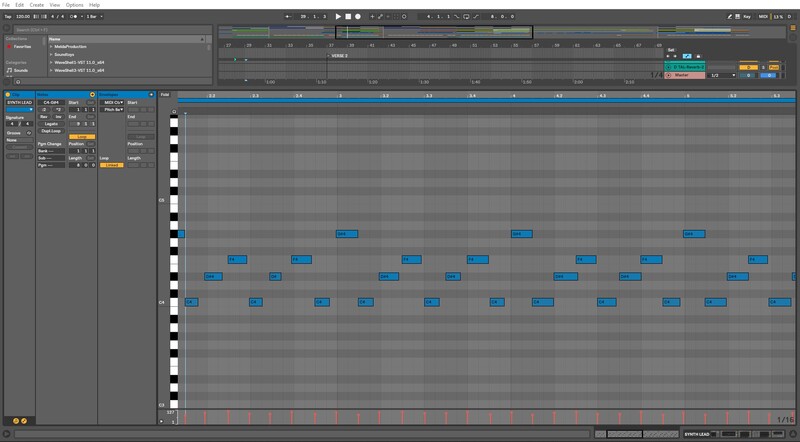

Tip: If you’re finding it difficult to come up with interesting rhythms, try loading a sample into Loopcloud and using the Pattern function in the sample Editor. Click + Add Samples… and then select a file from your computer’s storage. You can then choose a pattern from the Pattern dropdown menu, from a range of instrument and genre options.

Add ornaments

To jazz up your melodies, decorate them with musical ornaments, or notes that are added to embellish the main notes. Ornaments are common in classical music, where they function as a way of creating space for musical expression and showcasing a player’s virtuosity. However, they can be used in a much more simple sense to build upon a foundational melody.

Try adding super-short grace notes at the start of, just before or even in the middle of a longer note. Another ornament you could add to a melody is a trill; a quickly alternating pair of notes. Usually, a trill alternates between a semitone or whole step from the base note, so that it gives the impression of rapid fluttering.

If you have a MIDI keyboard, experiment with its pitch and modulation wheel to add extra ornamentation to notes while you’re recording. The pitch wheel can be used to add pitch bend, which can be either subtle or dramatic, and the modulation wheel is generally assigned to vibrato or a similar effect.

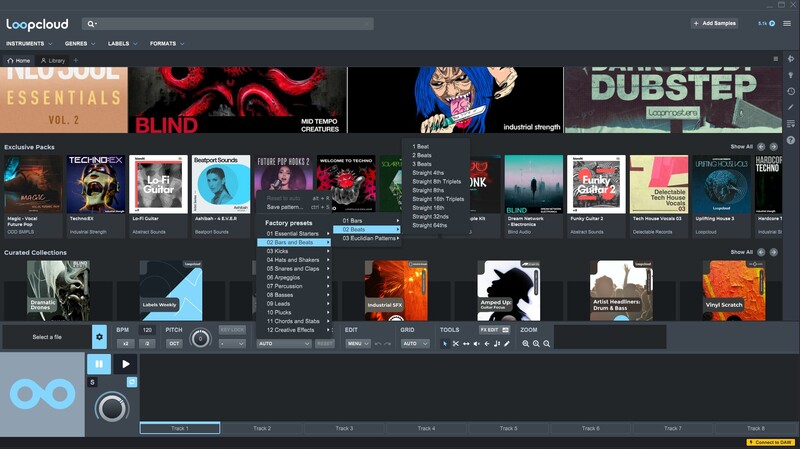

Evolve one-note rhythms

Sometimes to write a good melody you need to try methods of composition that are entirely different to your usual ways. One useful trick for beating writer’s block requires you to forget about melody altogether, and instead focus on trying to come up with a rhythmic phrase that complements the music you’ve already got.

Choose a note that’s in key with your song and program a rhythm that works within the context of the track using only that note. Once you’ve landed on something that you like, go through the phrase and move each note up or down to create a melody. Remember, you don’t have to move notes if you don’t want to – repetition is often a good basis for melody writing.

Fine-tune your melody by making adjustments to note length or removing notes entirely. After you’ve settled on a melody, you can add variation by repeating the phrase with different notes immediately after.

Change your hardware

A lot of producers prefer using analog equipment or actual instruments for their melody-writing sessions, rather than drawing in MIDI clips or other on-screen processes. This is in part due to the increased feel you get while jamming on a physical instrument, which is why it can be very helpful to switch back and forth from different hardware if you can.

Playing an instrument or programming an analog synthesizer takes skill and dexterity, but you don’t need to be Jacob Collier to get results. Often, unexpected gold can come in the form of happy accidents or mistakes you make while applying yourself to an instrument. Skill level will determine the upper ceiling of what you can achieve, but the way you arrange the furniture in the room below will be unique to you.

If you’re spending ages in the box and the melodies aren’t coming, try switching to hardware and seeing what comes. Rotate through whatever instruments or equipment you have available to you, regardless of your skill level. Each one will force you to do different things, which will lead you down new creative avenues.