Blog

Ultimate Guide to Types of Microphones For Music Makers

30 Dec '2024

Get to know the difference between dynamic and condenser mics, plus know when and how to use lav mics, shotgun mics and consumer-grade USB mics with this guide

Many people have never considered the humble microphone. They’re too focused on the person holding it or the instrument it’s pointing into. But while the audience is blissfully ignoring this piece of musical equipment, the musicians, producers and live engineers often know better. Like a guitarist selects their guitar, a singer will often have a favourite microphone that “goes with” or “just works” for their voice. That could be down to the unique combination of circuitry and design at hand… or maybe just because of how it looks makes them feel as they perform with it.

In this article, we’ll take you from the knowledge level of that unassuming audience member, and give you the ability to choose a microphone for yourself – whether you’ll be singing into it, or using it for any other purpose. We’ll cover what different microphone types there are, what that means in practice, and what might make you want to choose one over another. We’ll explain technical terms in a simple manner and illustrate our concepts with photographs and simple diagrams.

In this article

Quick recap: what is a microphone?

Dynamic vs condenser microphones

What’s the difference between dynamic and condenser microphones?

How can you recognise a condenser or a dynamic microphone?

What are the advantages of dynamic microphones?

What are the advantages of condenser microphones?

Other microphone types – ribbon, piezo and more

Piezoelectric (crystal) microphones

Microphone types through polar response pattern

Microphone types through form factor – shotgun mics and lavalier mics

Lavalier microphones (tie clip mic)

Microphone types through connectivity – USB vs XLR mics

Quick recap: what is a microphone?

We won’t make this a huge section, because you already know on one level what a microphone is. But a more technical definition will help at this point. A microphone is a transducer, which is a fancy way of saying that it turns one type of energy into another. In this case, it turns the energy carried in the movement of air (sound) and turns it into electrical energy.

Your speakers are transducers, too – only they’re turning electrical energy into sound in the opposite order performed by a microphone.

So if a microphone acts as a transducer, turning sound energy into electrical energy, then how specifically does it do this? Read on to discover that the different method define our first two ‘types’ of microphone.

Dynamic vs condenser microphones

These two microphone types are a very broad way of splitting almost all microphones (we’ll go through the exceptional microphone types in the next section). Dynamic and condenser microphone types probably cover 95% of professional microphones used on stage or in the studio, and so they’re a good place to start.

Dynamic and condenser microphones use two different principles to turn sound in the air into an electrical signal.

What’s the difference between dynamic and condenser microphones?

In a dynamic microphone, a magnet moves through a coil to induce a voltage. In a typical case, the coil is fixed and the magnet is able to respond to the moving air (sound) that hits it. These movements are pretty much too small for us to see, but they’re big enough to create a voltage signal as the magnet moves through the coil.

Condenser microphones use either two charged plates or a single charged plate with a conductive membrane. That membrane (or a single, lightweight plate) is allowed to be moved by the incoming air (sound), and this creates a difference in air pressure and charge between the two elements. This leads to an electrical signal that follows the pattern of the sound. Condenser microphones must be given power (aka “Phantom Power”) in order to actually work.

How can you recognise a condenser or a dynamic microphone?

This isn’t such a straightforward topic, as two very similar looking microphones can often be different types. Perhaps the most famous microphone in the world, and the one most people think of when they think of a microphone, is the Shure SM58, which is a dynamic microphone.

The SM58, its sibling the SM57, and the modern companion and podcaster’s favourite, the SM7B, are all dynamic microphones. Given their construction, nothing makes it obvious that they’re dynamic rather than condenser microphones, and so recognising these three mics in the wild is a consistent way of spotting a dynamic microphone.

Image by Pixabay on Pexels

On the other hand, a condenser microphone can be set up in a more flexible arrangement, not needing a coil or magnet to generate its sound. You’ll almost always find that very small microphones (lav or lavalier mics, which we’ll talk about later), are condenser types, as are short and stubby mics, as well as long and sticky shotgun types.

You can often recognise a condenser microphone on inspection by a sign saying 48V or Phantom Power, as these microphone types require this power to operate.

What are the advantages of dynamic microphones?

Dynamic microphones are more rugged and hard to break, making them more likely to survive the proverbial ‘mic drop’. Dynamic mics can also usually withstand a higher sound pressure level (IE volume) before they distort or cease to operate properly.

To balance these advantages, dynamic microphones cannot be squeezed into a small form factor, may struggle to pick up small details in loud environments, and tend to sound slightly duller in the higher frequencies (treble).

To summarise, the advantage of dynamic microphones are:

- More rugged and droppable

- Can take a higher volume of sound input

- Great for stage and live use

- Last for a long time

- Don’t need phantom power

Image by Pixabay on Pexels

What are the advantages of condenser microphones?

Condenser mics are usually more sensitive, meaning they’re able to pick up more details. A condenser microphone’s architecture usually means that it can be ‘squashed’ into a small size to act as, for example, a lavalier or “tie clip” microphone.

On the other hand, a condenser microphone requires a source of 48V phantom power to run, can pick up more background noise due to its sensitivity, and may not be as rugged and durable as a dynamic model.

- To summarise the advantages of a condenser microphone, they are usually:

- More sensitive to sound

- Able to pick up more minute details

- Available in smaller sizes

- Generally a little more versatile for diverse applications.

Image by Amin Asbaghipour on Pexels

Other microphone types – ribbon, piezo and more

While almost all professional microphones for musical applications can be divided into the categories of condenser and dynamic, there are some other types of microphone out there that it’s worth illuminating.

The humble ribbon microphone was once popular for its ability to drown out sources that weren’t its speaker, then fell out of fashion for its talent for breaking quite easily. These days, strategies have been developed to make nearly indestructible ribbon microphones, so it’s worth mentioning this as an option.

Ribbon microphones work using a thin, lightweight strip of metal (IE, the ribbon) suspended between two magnets. When the ribbon moves, it creates an electrical signal through electromagnetic induction.

This type of microphone is known for its smooth frequency response, and has a natural figure-eight polar response due to its flat ribbon, which requires sound to hit head-on for best effect. We’ll cover polar response patterns later on in this article.

Piezoelectric (crystal) microphones

Certain materials response to pressure and stress by release a voltage, and this effect – known as the piezoelectric effect – has been used as the basis for a whole category of microphones. Piezoelectric mics are rugged but can give a very harsh sound especially when pushed to extremes.

Also sometimes called a PZM or ‘pressure zone’ microphone, a boundary mic goes on a large, flat surface, and can be placed on a wall or table. These mics can be great for capturing ambient sound in music, but are often more suited to the conference room or auditorium.

These mics are the only ones we’re mentioning that don’t actually pick up sound from the air! Instead, contact microphones are mounted onto a surface, picking up the sound that travels through that surface. This makes contact mics good for capturing ambient sound when placed on an actual surface, or potentially useful for recording instruments like acoustic guitar or piano when placed on the actual instrument.

Microphone types through polar response pattern

Not every direction is treated equally by every microphone. You may know that you have to sing ‘into’ a microphone for it to work its best, and with some mics this is particularly important, as they will reject sound that comes at them in any other direction.

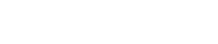

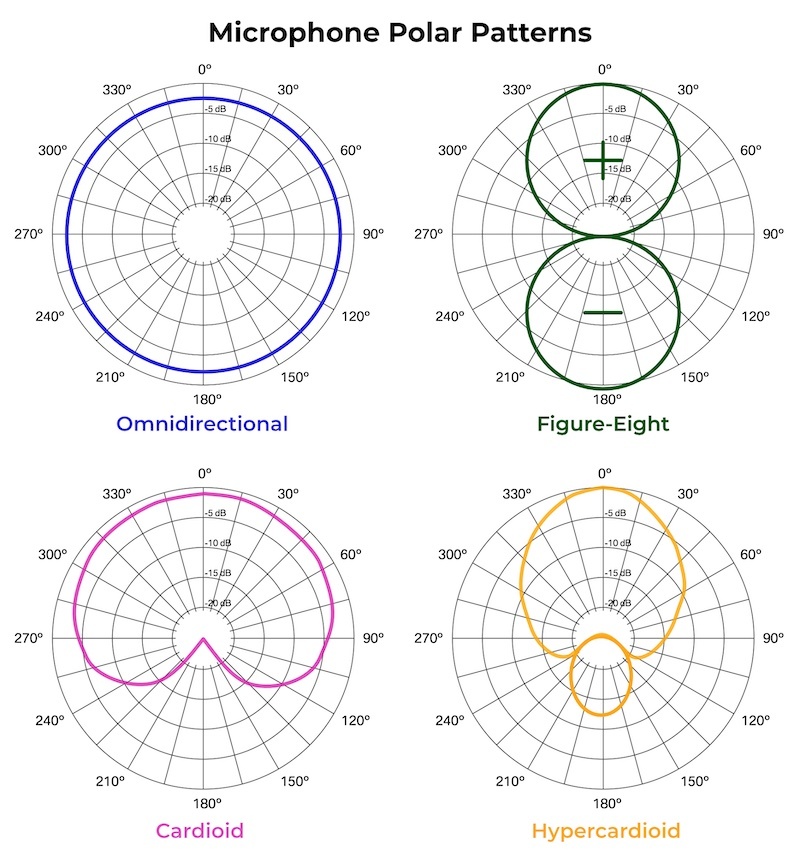

Below are the four main types of microphone in terms of their polar response. The omnidirectional, in blue, picks up sound in all direction equally. The figure-eight mic has strong front and back acceptance, but doesn’t pick up much at the sides (like the ribbon microphone mentioned earlier).

If you combine an omnidirectional polar response with a figure-eight by literally adding their responses together, then thanks to the figure-eight’s positive and negative lobes, the result is the cardioid microphone. This microphone polar response type is actually a very likely one to encounter – the Shure SM57 and SM58 dynamic microphones are cardioid types, a fact which makes them even more suited to use on the stage.

Finally, a hyper-cardioid response type is the sort of highly directional pickup pattern you’d expect to see in a shotgun or boom microphone – as explained below.

Microphone types through form factor – shotgun mics and lavalier mics

The following microphone types may be categorised as dynamic, condenser, both or anything else. Our point here is to distinguish microphone ‘types’ not from the mechanisms that make them operate, but instead from their shape, build and usage.

This type of microphone is intended for picking up sound in a hyperfocused way. Point a shotgun mic at a source of sound, and you should hear that source of sound. So far so normal! But the specific thing about a shotgun microphone is that you shouldn’t hear very much at all of the other sounds around it.

A shotgun microphone is highly directional, accepting sound travelling towards its front (IE what it’s pointed at), but rejecting sound coming from the sides. This makes this microphone type great as a ‘boom mic’, mounted to a camera, or for any other similar use case in film and TV, where you want to point at a single source and get nothing else bleeding into your signal. (Ideally at least).

Image by Luis Quintero on pexels

Lavalier microphones (tie clip mic)

A lav mic is something you may have seen (whether you realise it or not) on TV or YouTube. A presenter can be ‘miked up’ without having a shaft of metal shoved in their face. In fact, with a lavalier mic, multiple people can be wired for sound without it being very apparent to the audience. That’s because the lav mic type (or ‘tie clip mic’), is small, portable and able to be hidden.

The advantages of a lav mic are clear: the size makes the mic somewhat invisible. The disadvantage is when this type of microphone goes wrong, as stiff clothes can brush the lavalier mic (sometimes called a ‘Pin Mic’) and create a rough, unwanted noise.

Microphone types through connectivity – USB vs XLR mics

The standard way for professional microphones to connect has generally been through XLR connection. This required microphones to be plugged into an external audio interface before their signal could be digitised and accessed by your computer.

However in recent years, the popularity of USB has been compelling enough for manufacturers to produce microphones which digitise the signal right inside the device, giving you an immediate USB output.

A USB-ready microphone, however, will often suffer from poor sound quality if cheap analogue-to-digital converters (ADCs) have been used. For professional application, XLR-connected microphones are usually a safer bet.